As late winter maple tree tappings give way to spring celebrations of Easter and Arbor Day, Garrett County residents are bidding farewell to another season of snow. Although the most recent winter ranks as more temperate than many, those living and vacationing in the state’s most western county can be described as people of perseverance who also hold a deep appreciation for the vast beauty and recreation of the region.

Perseverance as a character trait certainly marks one of Oakland, Maryland’s most successful native sons. Were it not for the steadfast commitment of his parents to help their child overcome a disability not understood in his early 20th-century childhood, Karl Victor Kahl may not have become a highly successful engineer with a belief in the transformative power of education.

Born in Oakland in 1929, Kahl, known affectionately as KV, excelled at mathematics and anything involving numbers and mechanics. Born to Karl Frederick Kahl and Mabel Falkenstein Kahl, young KV was an inquisitive and intelligent child, so naturally, it was perplexing to both his parents that he struggled to learn to read.

Later diagnosed with dyslexia, Kahl was lost in the public school system which was largely under-equipped at the time to deal with the challenges he faced. “His teachers told his parents that KV wasn’t very bright. He was bullied by his peers. “He told me many times that he often felt like he was stupid when he was in school. It was the most difficult time of his life,” recalls his niece Kathy Snyder, an attorney practicing in West Virginia.

Despite innate abilities obvious to his parents, his life without their support could have been far less productive. Refusing to accept that their son could not read, his parents searched for help and found the Perkiomen School in Pennsylvania where there were teachers who could help him.

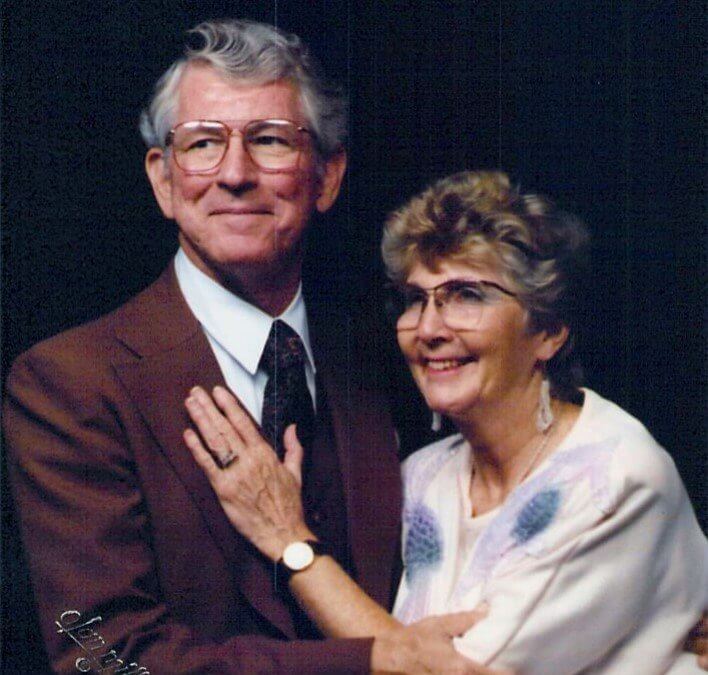

With the full support of his father, Kahl and his mother packed up and moved to eastern Pennsylvania for two years so that KV could complete high school in 1950 at the age of 21. After completing high school, Kahl continued his studies at Potomac State College where he met the love of his life, Haseleah “Hassie” Snyder. KV earned an associate’s degree in engineering while Hassie completed a degree in business administration and secretarial science. Shortly after they were married, Kahl was drafted into the Army.

Upon discharge, he returned to West Virginia University to complete his formal education in 1957 with a bachelor of science degree in civil engineering, including several courses in structural design. Kahl is reported to have said “they” earned the degree as he was quick to credit Hassie as sharing in his education since she read his textbooks to him, helped him take notes, and study every night.

Fortunately for Kahl, the region, and future students, he received the intervention needed to set his life on a course of future success. Eventually becoming an accomplished engineer, Kahl spent 30 years designing and maintaining roads and bridges across the tristate. Earning numerous awards and accolades throughout his career, he was often consulted, even in retirement, for advice on bridge structure and design.

Retiring in 1988, he returned to his humble life in Oakland, Maryland. Living well within their means in the same three-bedroom house where KV grew up, his only indulgence was his love of cars and tractors. “He had some very nice ones, but nothing too flashy,” Snyder reminisces. “They ate at Englanders and shopped at Walmart. They were the living embodiment of the millionaire next-door that Tom Stanley wrote about.”

Kahl’s struggles with dyslexia led both him and Hassie to place a high premium on education. With no children of their own, they helped their nieces and many other Garrett County young people pursue higher education and technical training.

“When I was starting law school, they drove to Morgantown to see me. They told me they were going to send me a check every month so I could quit my part-time job at the grocery store and focus on my studies. Their generosity inspired me to study harder,” recalls Snyder gratefully.

Both he and Hassie believed that education was the means by which a person could choose to change his or her circumstances. Therefore, prior to his death, Kahl looked to the Community Trust Foundation (CTF) to ensure their legacy would be perpetuated.

Creating the Karl V. and Haseleah Kahl Scholarship Fund at CTF met the couple’s desire to provide scholarships in meaningful amounts to students who have overcome significant challenges and also demonstrate a commitment to learning and a work ethic predictive of success, whether they have achieved high, average or even below-average academic achievement.

CTF executive director Leah Shaffer notes, “The Kahls believed that modest talent is often overcome by passion, commitment, dedication, and hard work and that such students should be eligible to receive scholarships so that they too have the opportunity to pursue an education.” CTF helps people like the Kahls support the causes they care most deeply about to create the greatest possible community good.

While the Kahl gift was one of the most generous the Foundation has received, CTF board chair Marion Leonard adds that leaving even a small portion of an estate to philanthropy can have a ripple effect for years to come. “Many people plan to leave their assets to their family which is a fine motive,” Leonard explains. “However, designating even 5% of one’s wealth in estate planning for the good of the community can perpetuate a legacy far beyond one’s imagination.”

Despite progress made in the late-20th century to remove barriers for people with disabilities, much remains to be done to ensure future students can learn and thrive. The persistence of an Oakland mother to educate her misunderstood child seeded determination and endurance in her hard-working son, ultimately leaving a legacy of perseverance, philanthropy, and hope.

Much like the solid structures of concrete and steel he erected over the region’s countryside to enable vehicular mobility, his generous gift to the community serves as a bridge to opportunity for countless students he would never meet.

“Not bad for a kid who couldn’t read,” he often quipped.

CTF is building a more vibrant community by connecting philanthropy for community good in our region of Allegany, Garrett & Mineral Counties. ctf@ctfinc.org, 301-876-9172, or visit www.ctfinc.org